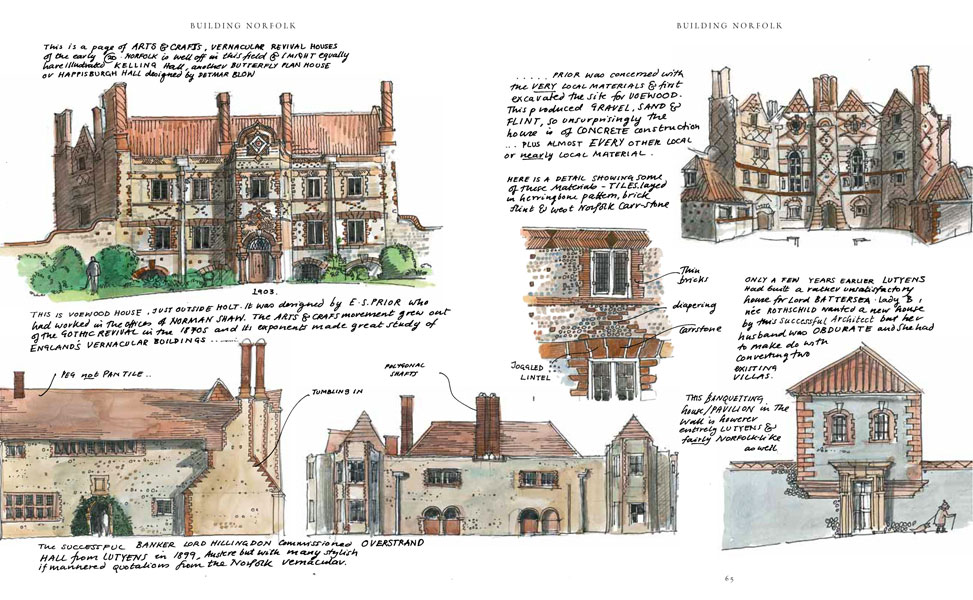

Matthew Rice’s book ‘Building Norfolk’ attracted quite a lot of attention when it was published last year; not surprisingly. It is a beautiful book full of exuberant, colourful drawings. I could write a whole other post, lamenting the death of hand-drawn images in architecture or even one agreeing with Rice’s preference for drawing over photograph in capturing the essence or character of a building. Instead I’m going to be a bit critical.

There’s plenty in the book I recognise, even a few individual buildings, but overall it seems to me the book places too much emphasis on the ‘high-road’ buildings I talked about in the last post. True, there are chapters at the start about ‘Vernacular Building’, ‘Cottages’ ‘Village Houses’ and ‘Farm Buildings’ but all too quickly we’re into ‘Manor Houses’, ‘Country Houses’, ‘Estate Buildings’, ‘Parsonages’…and, on one level, fair enough, I guess. If I produced a book with pages and pages of fairly similar small houses, a good number of fairly similar barns and a smattering of churches, I’m confident it wouldn’t capture the imagination like ‘Building Norfolk’ – even if illustrated by Rice; but there is a danger that we over-romanticise the vernacular, or worse, confuse the vernacular with the architecturally ambitious (in other words confuse ‘low-road’ and ‘high-road’).

There’s plenty in the book I recognise, even a few individual buildings, but overall it seems to me the book places too much emphasis on the ‘high-road’ buildings I talked about in the last post. True, there are chapters at the start about ‘Vernacular Building’, ‘Cottages’ ‘Village Houses’ and ‘Farm Buildings’ but all too quickly we’re into ‘Manor Houses’, ‘Country Houses’, ‘Estate Buildings’, ‘Parsonages’…and, on one level, fair enough, I guess. If I produced a book with pages and pages of fairly similar small houses, a good number of fairly similar barns and a smattering of churches, I’m confident it wouldn’t capture the imagination like ‘Building Norfolk’ – even if illustrated by Rice; but there is a danger that we over-romanticise the vernacular, or worse, confuse the vernacular with the architecturally ambitious (in other words confuse ‘low-road’ and ‘high-road’).

Rice does include a few ‘modern’ buildings, but mostly in a disparaging way. Again, fair enough: there aren’t lots of great C20th buildings in Norfolk and those that do exist can’t really claim to be regionally distinctive. I can see why Rice isn’t that interested in the 1950s and 60s chalet bungalow, except to poke fun at it, but I would suggest that the almost total absence of brick-built 30s and 50s council-housing is a serious omission. Like the 60s chalet-bungalow it is ubiquitous and a key part of Norfolk’s rural streetscape, but I think you could argue it is also quite regionally distinctive.

However, by the end of the book it emerges that Rice has a clear position on how we should build today; we understand why the book is called ‘Building Norfolk’ rather than ‘Norfolk’s Buildings’. Rice not only dismisses the Modern Movement and its watered-down legacy in the county, but he is almost equally dismissive of modern house-builder pastiche. In a passage about the Buttlands in Wells-Next-the-Sea he focuses on a group of five houses built in 1993 in a fairly in-offensive neo-traditional style, and proceeds to illustrate how it could be ‘improved’: a break in the roof line here, some variety in frontage width there, a string course on one house, some assymetry in the gable of another. Rice’s reasoning is bleak:

Current developments are less austere, decoration has crept back, and even the standard appearance of a housing association estate is now enfeebled Victorian. If we are to remain culturally backward-looking, would it not be better to work fluently and creatively in the language of tradition than to imitate it superficially and ineptly?

Well, maybe…but better still if we refused to remain ‘culturally backward-looking’ and instead face up to the challenge of developing a sensitive, modest and regionally distinctive approach to contemporary design.

More on regional distinctiveness next.

More about ‘high-road/low-road’ buildings here.