In a previous post (way back in October!) I wrote about the wide-fronted house, the third of four ‘rural archetypes’ I described during the tour of Norfolk I did for Beyond Green last summer. I explained that the three- then two-celled cottage evolved from the mediaeval hall-house to become the standard configuration for the rural house in Norfolk (indeed much of Britain) during the seventeenth and eighteenth century. During the nineteenth century industry replaced agriculture as the power-house of the British economy, and the focus for innovation in housing design moved from the countryside to the city.

The challenge for the factory-owner was to accommodate his workforce within walking distance of work. The terraced house made better use of land than the free-standing cottage, and offered considerable savings in build-cost through sharing each gable-wall between two houses. The store, kitchen and parlour arranged parallel to the road in the traditional rural house were turned through 90°, so the wide-fronted house became the narrow-fronted terraced cottage, with the parlour at the front on the street and the kitchen at the back. The terrace format also offered savings in the reduced length of road and sewer (if provided!) per unit compared to a wide fronted house of similar size. So commercially advantageous was the terraced house that by the end of the nineteenth century (estimates Stefan Muthesius in The English Terraced House) it made up over 85% of the country’s housing-stock.

The challenge for the factory-owner was to accommodate his workforce within walking distance of work. The terraced house made better use of land than the free-standing cottage, and offered considerable savings in build-cost through sharing each gable-wall between two houses. The store, kitchen and parlour arranged parallel to the road in the traditional rural house were turned through 90°, so the wide-fronted house became the narrow-fronted terraced cottage, with the parlour at the front on the street and the kitchen at the back. The terrace format also offered savings in the reduced length of road and sewer (if provided!) per unit compared to a wide fronted house of similar size. So commercially advantageous was the terraced house that by the end of the nineteenth century (estimates Stefan Muthesius in The English Terraced House) it made up over 85% of the country’s housing-stock.

You do find the occasional short run of terraced cottages in Norfolk, but they are not common. The process of enclosure and mechanisation which began in the eighteenth century continued through the nineteenth, leading to massive rural de-population as workers flocked to the cities and towns in search of work. Relatively few houses were built in the countryside in this period, so the new-fangled ‘terrace’ format didn’t become wide-spread.

Meanwhile conditions in cities for industrial workers deteriorated steadily during the C19th, to the point that illness and vice amongst the working classes started to threaten their productivity and political passivity. Early efforts to improve the situation – by Peabody, Rowntree, Guinness and the Garden City movement – gained momentum as the government geared up for war, and then peace after 1919. The real fear of a Bolshevik-inspired workers’ revolution prompted a thorough review of housing-standards, which culminated in the Tudor Walters Report of 1918.

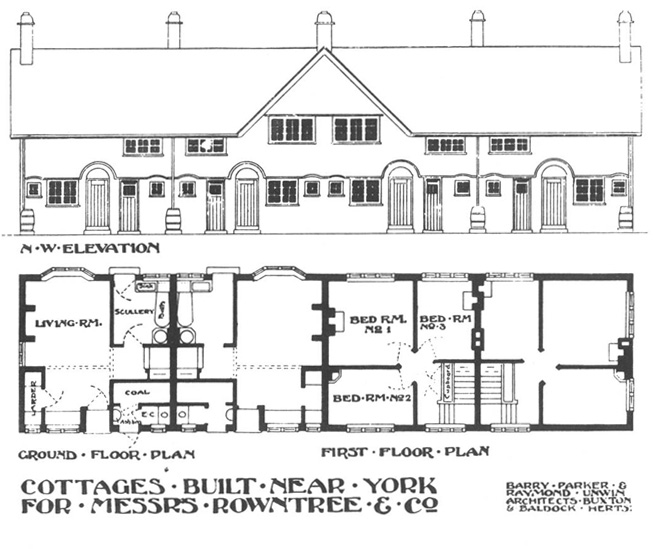

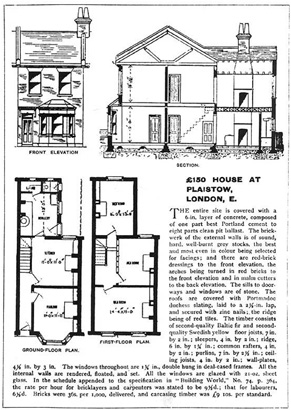

The housing committee led by John Tudor Walters drew heavily on the work of the Garden City movement and its pioneering architects Parker and Unwin who had given a lot of thought to how the workers cottage could be improved (not least because Raymond Unwin was on the Committee). One of their key recommendations, enshrined in the the Report, was to try to get sunlight into the principle room – the kitchen – of every house. In the classic urban terraced cottage, the parlour (reserved for special occasions and show) occupied the street frontage, while a combined kitchen/living room was located at the back, often cramped by a single-storey rear wing containing coal store and WC (see pic above). If the house was located on the north side of street, this principal living space would face north, and never receive direct sunlight. Parker and Unwin developed cottage plans that did away with the parlour, which they considered largely redundant, in favour of a single living room opening right through the house, front to back, so that no matter which side of the street it was arranged it would always receive sunlight (below).

Despit the clear advantages of this wider-fronted through-room arrangement, the narrow plan with ‘front’ and ‘back’ rooms proved very enduring…as I will describe in the next post.